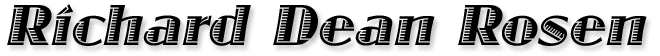

Curiosity about my childhood neighbor Sid Luckman, the Hall of Fame Jewish quarterback who led the Chicago Bears and the National Football League into the future in the 1940s, led me to an astonishing discovery: his Russian immigrant father had gone to Sing Sing Prison on a second-degree murder conviction in 1936 and never seen his famous son play in either college or the pros. A single Brooklyn family had produced the most important Jewish pro football player in history and a homicidal associate of the powerful Brooklyn mobster, Louis “Lepke” Buchalter. Just as astonishing, the father’s brutal crime, which had made front-page headlines in New York for years and helped to bring down that era’s Syndicate, was soon forgotten, suppressed by a respectful media and by Sid Luckman himself. Only a single old man’s memory kept the crime alive, and eventually made possible Tough Luck, which is unique in the annals of sports crime stories, and surely one of the most Shakespearean true-life father-son tales ever.

(Click on cover to purchase)

PRAISE for Tough Luck

“…a great and beautifully written untold story.”

—Gay Talese

“A magnificent book.”

—Marv Levy, Pro Football Hall of Fame Coach

“Remarkable….As compelling a book as I’ve read in a long time.”

—Rick Kogan, Chicago Tribune and WGN Radio

“With great research and storytelling, Rosen brings to life Depression-era New York and WWII-era Chicago in a wonderful family saga that will captivate history and sports fan alike”

—Publishers Weekly

“A terrific read that should draw interest from all general nonfiction readers.”

—Library Journal

“Vigorous storytelling at the intersection of crime and sports history.”

—Kirkus Reviews

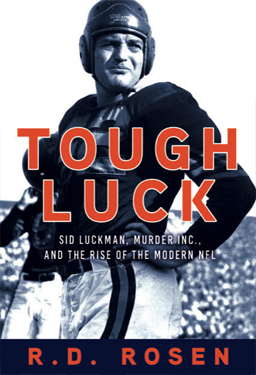

Serendipity has played a huge role in my book-writing. I wish I could say I always set out to write books that satisfy a conscious curiosity or fulfill a long-standing ambition, but the truth is that a chance meeting will activate some inchoate desire to explore a topic or theme. Before meeting Veryl Goodnight and Roger Brooks in Santa F in 2002, I had given no thought to writing about buffalo or the American West. Before meeting Sophie Turner-Zaretsky at a Passover seder in 2010, the thought of writing about the Holocaust had not crossed my mind. Afterwards, I felt oddly destined to write her story and those of two other hidden child survivors, and, in doing so, remedy a nagging ignorance about the destruction of my own people during World War II.

Here again, as with A Buffalo in the House, I was drawn to the repercussions of the traumatic past on the present. While the vast majority of Holocaust books concentrate on the Holocaust experience itself, in the case of Such Good Girls I sought to tell not just the stories of how three girls survived the Holocaust in three different countries, but how the horrors of their childhoods affected them—and other hidden child survivors, the last living eyewitnesses to Hitler’s Final Solution—throughout their lives. It seems self-centered to say that researching Such Good Girls and interviewing the subjects in depth was emotionally taxing, given the tragic realities of my subjects’ childhoods, but no one even writes about the Holocaust unscathed.

“Most powerful of all,” wrote the Wall Street Journal, “[Rosen] makes us see how the Holocaust’s hidden children succeeded against the odds not just once, by surviving, but twice, through the resonant new lives they subsequently forged.” Such Good Girls actually made it for a week into the #1 spot on the New York Times E-Book Best Sellers list.

(Click on cover to purchase)

A chance meeting with a large mammal chiropractor in Santa Fe, New Mexico, led me to this story about a childless couple that adopted an orphaned buffalo calf. The wife, Veryl Goodnight, a well-known Western sculptor of animals, needed a baby buffalo to pose for a sculpture of her ancestor Charles Goodnight, who, in the 19th century, help saved the American buffalo species from extinction. The chance to connect a contemporary animal love story—Veryl’s husband Roger fell head-over-heels for Charlie—to the 19th-century genocide of the American Indians and the massacre of the tens of millions of buffalo their existence depended on—was irresistible to me.

From the cover:

“Surrounded by people and dogs, Charlie has no idea he’s a buffalo—and Roger has no idea how strong the bond between a middle-aged man and a buffalo can be. When Charlie’s later introduction to a herd results in a terrible accident, Charlie’s courage and Roger and Very’s devotion are pushed to their limits.

“Contrasting the nineteenth-century killing of tens of millions of buffalo against our own era’s environmental consciousness, this book asks the question: How far are you willing to go for an animal you love? A love story, a comedy, and a history of the American West, A Buffalo in the House packs a major emotional wallop and will be hard to forget.”

(Click on cover to purchase)

PRAISE for A Buffalo in the House

“More than a touching man-beast buddy tale…Rosen lovingly chronicles the history of an embattled species and its importance in the American West.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“Riveting…From the story of one stray baby bison named Charlie…and the family that took him in, Rosen has drawn a sweeping history of the American frontier…I can’t remember when I’ve been instructed so gracefully, or entertained to such deep purpose.”

—Jane Kramer, The New Yorker

“Powerful…[Charlie is] one of the most memorable characters in recent nature writing.”

—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Moving proof of the restorative powers of man’s relationship with nature.”

—People

Having invented the word “psychobabble” in 1975 [see the MY WORD section for more], I went ahead and wrote this book, exploring the psychological and linguistic chaos caused by the proliferation of “alternative” therapies, psychiatric cults, and humanistic slang that had begun to adorn casual conversation everywhere like cheap and poorly-applied lipstick. Primal Scream therapy, Co-Counseling, Rebirthing, est, self-help literature, and even the first computerized psychiatrist came under my glib scrutiny.

Too heavily influenced by an older psychoanalytic model, and really much too young to be telling other people what to think and do, I was secretly ashamed of my chutzpah at the age of 27 and surprised that I was taken so seriously. Obviously, if I too hadn’t been ensnared in my own way by the maze of the psychotherapeutic process, I would never have been interested in writing a book on the subject. Nonetheless, I’m happy to report that time and experience have borne out the wisdom of my rejection of the era’s psychotherapeutic salesmanship.

(Click on cover to purchase)

Oy. At least I had the good sense to call this juvenile collection of essays I wrote at 21 “a premature memoir.” Some essays I’d written for The Harvard Advocate and The Harvard Crimson had caught the eye of Sam Stewart, an alum then editing for Macmillan Publishers in New York. A tiny book contract ensued. It was 1970 and the mainstream media were looking to us Baby Boomers to explain “the counterculture” to the rest of America.

Political ideology was not my strong suit, so I poured into the pages of Me and My Friends all the anti-bourgeois cultural observations I had accumulated in my years as a son of the post-World War II suburban bourgeoisie. What can I say? It taught me I could complete a book-length project, and “my friends” tell me it’s a respectable and revealing “period piece.” I wouldn’t know, since I’ve always been afraid to open the book and glimpse that cocky but confused version of myself, still years away from any true consciousness.